How Did the Affair of the Necklace Precipitate the French Revolution?

Marie Antoinette’s legacy will forever be overshadowed by the damning reputation that she was branded with during her life, resulting in her status as one of the most unfairly villainized women in history. Her frivolous fashion, taste for splendid excess, spending, and independence were all things she was scrutinized for throughout her reign. This notoriously lush lifestyle led to her being publicly blamed for the many issues facing France, and her being labeled with numerous unflattering nicknames like Madame Veto, Madame Deficit, and most sexist of all, L’Autrichienne, which likened her to an Austrian female dog. Though Marie Antoinette was able to navigate many of the defamatory rumors spread about her during her reign, the ones that stemmed from the creation of a 2,800-carat diamond necklace that she rejected numerous times would ultimately contribute to her death. The scandal surrounding this necklace accelerated the French Revolution, and by the end, both the necklace and the French monarchy would be broken beyond repair.

The affair of the necklace did not cause the unhappiness and dissatisfaction that the French people had with the monarchy, but it certainly helped amplify it. A huge portion of the population was suffering from poverty and this exorbitant piece of jewelry was easy for them to latch onto as a symbol that magnified ongoing class divides, economic uncertainties, and the unequal role of women in society. The diamond necklace scandal and trial that followed helped to propel the Revolution and seal Marie Antoinette’s fate at the guillotine. Hundreds of years later, these events continue to act as a dark cloud that will eternally cast a shadow over her legacy.

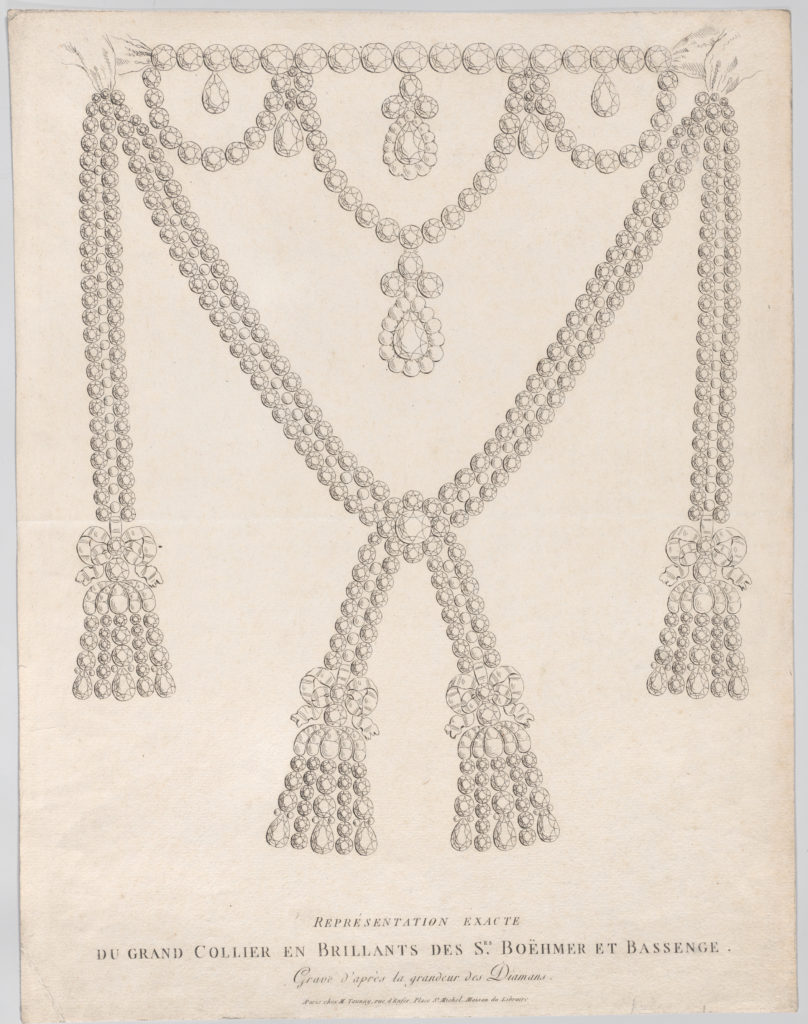

The Creation

In 1772, King Louis XV wanted to give his maîtresse-en-titre, Madame du Barry the most extravagant and expensive diamond necklace imaginable. The gift was meant to be a symbol of his devotion and one that du Barry could shamelessly flaunt at the royal court to show everyone how important she was to the king. To bring this necklace to life, Louis XV commissioned his court jewelers, Charles Auguste Boehmer and Paul Bassange. Trusting that the extraordinarily wealthy king would eventually pay them in full, the pair spent around 200,000,000 livres of their own funds on the materials needed to create the piece. After two grueling years of amassing the hundreds of diamonds required to complete the necklace, King Louis XV unexpectedly died of smallpox, leaving them bankrupt and with no home for the most grandiose piece of jewelry they had ever created (Répresentation Exacte Du Grand Collier En Brillants Des Srs. Boëhmer Et Bassenge Ca. 1785). This magnificent necklace must have shimmered as brightly as Versailles’ hall of mirrors with its 540 round and pear-shaped diamonds. The top portion was described by Thomas Carlyle as having “a row of seventeen glorious diamonds, as large almost as filberts…looser, gracefully fastened thrice to these, a three-wreathed festoon…” (26). Pale blue ribbons acted as a closure, allowing the upper half to be worn separately from the bottom portion. The V-shaped lower half of the piece also secured around the neck with ribbons. This is the most eye-catching, memorable, and unique part of the design due to its geometric shape and the four tassel-like diamond fringes, each topped with a delicate blue bow.

A Complex Scheme

It must have been heartbreaking for Bassange and Boehmer to have this work of art left deserted in a box after all of the money and time they had invested. Their necklace oozed with unapologetic extravagance, and the jewelers figured that only someone as rich and over the top in their fashion choices as Marie Antoinette would be able to afford or wear such a thing. During the ancien régime, barely anyone outside of the royal court could afford such an extravagance. With their target customer in mind, Bassange and Boehmer desperately tried to sell their necklace to King Louis XVI in 1778. When he offered the piece to Marie Antoinette, she was already well aware that the necklace had been made for Madame du Barry whom she despised. The new queen turned it down and considering the price tag used the more diplomatic excuse that “We have more need of ships than diamonds” (Fraser 227).

Bassange and Boehmer seized a second opportunity to try and sell the necklace to Marie Antoinette in 1782, shortly after she had given birth to the Dauphin, but it was turned down again. Around this time, a woman named Jeanne de Valois-Saint Rémy started to seek out Marie Antoinette in hopes to have a more generous pension approved based on her royal heritage. She claimed her grandfather was the illegitimate son of King Henry II, but despite having royal Valois blood, Jeanne had grown up extremely poor. It was only after a genealogist at Versailles confirmed her ancestry that she began to receive a meager stipend from the king (Haslip 165).

When Jeanne married Nicolas-Marc de la Motte in 1780, they proclaimed themselves Comte and Comtesse de Valois la Motte to try and enhance their social status and prove their nobility. The Comtesse salivated over the idea of becoming a more powerful part of society and visited Versailles often to try and get the attention of the Queen, hoping that another woman would be more likely to show sympathy for her financial situation. Her attempts failed and the two never met, but she started telling anyone who would listen that she was a close confidant of the Queen. Hungry for power, in 1783 de la Motte met Cardinal Louis de Rohan and became his mistress. He confided to her that he badly wanted to win back Marie Antoinette’s approval because she had been shunning him ever since he tried to prevent her marriage to Louis XVI (167). Having heard that Boehmer and Bassange were still trying to sell their necklace, de la Motte devised a scheme to use it to get rich involving her husband and her other lover Rétaux de Villette who also happened to be a master forger. Since de la Motte had already convinced the Cardinal that she was very close to the queen, she began to have de Villette forge letters from Marie Antoinette that stated she wanted to buy the necklace but due to France’s financial situation, she could never do such a thing publicly. The letters requested that the Cardinal purchase the piece on her behalf and implied that his doing so would put him back in the queen’s favor. He believed these letters were real, and de la Motte went as far as arranging a late-night, in-person meeting with the Cardinal and prostitute Nicole Le Guay d’Oliva who agreed to impersonate the queen for a payment of 1,500 francs.

Illusion Accomplished

In the summer of 1784, blanketed in the shadows of the Versailles garden, this Marie Antoinette lookalike handed the Cardinal a rose, assured him of her forgiveness, and confirmed his new standing with the court. To add to the illusion, she wore a veil and dressed in a chemise a la reine, which was a look popularized by Marie Antoinette years prior. Before enough time passed for the Cardinal to suspect the woman was not the Queen, de la Motte interrupted by saying someone was coming, causing everyone to flee the garden.

After what he thought had been a successful meeting with Marie Antoinette, the Cardinal proceeded to arrange a deal with Boehmer and Bassange, using the forged letters to prove to them that Marie Antoinette had finally changed her mind about the necklace. The jewelers were so thrilled to finally be able to sell their masterpiece and even agreed to a price cut. It was decided that the necklace payment would be made in four installments, totaling 1.6 million livres over the course of two years (The Affair of the Diamond Necklace 1784-1785).

Dismantled

Boehmer and Bassange last saw the piece of jewelry that had caused them so much misery and made them penniless when they handed it over to Cardinal de Rohan on February 1, 1785. He then passed it on to de la Motte who promised that she would deliver it directly to Marie Antoinette. Instead, she gave the necklace to her husband who had the piece dismantled and sold all of the diamonds “on the black markets of Paris and London” (The Affair of the Diamond Necklace). The de la Motte’s complicated scam unraveled quickly when Boehmer and Bassange wrote to the Queen in July of 1785 referencing their financial arrangement. They explained how happy they were to be of service and added “We have a real satisfaction in the thought that the most beautiful set of diamonds in the world will be at the service of the greatest and best of Queens” (Fraser 227). Marie Antoinette was baffled by what they meant and burned the letter thinking the jewelers were once again trying to solicit her to buy jewelry she didn’t want. The Cardinal was also becoming baffled that the Queen hadn’t worn the necklace yet or kept her word on granting his new status. Boehmer doubled down on accusations that the Queen wasn’t keeping her promise and revealed more details about the Cardinal’s letters to the court. King Louis XVI was furious when he heard about the situation and summoned the Cardinal for questioning. He explained what he knew about the situation, and everyone involved in the scheme was quickly apprehended. Marie Antoinette was mortified and furious that her reputation was tarnished by something she had not even been a part of. She was also aghast that de Rohan believed she would exchange such private letters with him considering their rocky relationship. Most insulting of all to the Queen was that Cardinal de Rohan had mistaken a hooker for her.

The Aftermath

The public was shocked by the arrest of de Rohan, and due to the general dislike for Marie Antoinette, rumors about her actual involvement in the situation began to grow. People speculated that she had the Cardinal arrested as revenge for their long-standing feud, and that she actually had secretly tried to buy the necklace. To make matters worse, the scandal was erupting “at the very moment when the French public was gaining new information both about the woeful state of the national economy and about the shocking extent of the Queen’s clothing expenditures” (Weber 164). Respect for the monarchy was diminishing quickly, but even so, the King and Queen pushed for a public trial in an effort to clear Marie Antoinette’s name and rehabilitate her reputation. They wrongfully assumed that everyone would sympathize with her having been the target of such an involved scam. Their plan backfired when instead, the public turned on Marie Antoinette and weaponized the opulent necklace against her. Reflected in those massive glistening diamonds was everything the French despised about the ancien régime. It must have been disheartening to have the monarchy place its focus on such a frivolous concern while so many people in the country were struggling to put food on the table. The fact that they would prioritize proving the Queen’s innocence over trying to help the country infuriated an already unhappy population. Even Napoleon recognized what a bad idea taking this route had been. He commented that “The Queen was innocent, and, to make sure that her innocence should be publicly recognized, she chose the Parliament of Paris as her judge. The upshot was that she was universally regarded as guilty” (Zweig 243). By the time the high-profile trial ended, Nicholas de Monte and Rétaux de Villette were exiled, and “although the public sympathized with her rather than with Marie Antoinette, Jeanne was sentenced to be whipped, branded, and imprisoned for life” (Collections Online: British Museum).

Even more of an insult to the Queen was that the Cardinal was acquitted. Katharine Anthony describes that “The trail of Cardinal de Rohan was subtly converted into a trail of the Queen, whom he hated. Marie Antoinette was found guilty of all of the absurd fictions which were marshalled [sic] in the prelate’s defense. Things which had not happened at all were laid at her door. The scheme worked with absolute success. Marie Antoinette took his place in the pillory” (162). Thanks to the trial whipping up popular hatred for Marie Antoinette, public opinion was more against her than ever before. While Jeanne de la Monte was branded with a hot iron to mark her as a thief for life, Marie Antoinette had been branded in a far more searing way. The vilification that stemmed from this trial signified a noticeable diminishment in the prestige of the monarchy. The public’s mentality had shifted dramatically and “Louis XVI was failing as a monarch every day more and more, and the rising tide of popular hatred would soon engulf him” (Anthony 163).

Glimmers of Change

The monarchy had been doing a terrible job dealing with the new social realities happening in the population, and things only got worse after drought led to poor grain harvests in 1788 and caused famine conditions. Almost 90% of the country’s population was struggling financially and the majority of their diets consisted of bread and cereals. Before the drought, poorer classes were spending around 55% of their income on these items, and afterward, they were spending nearly 85% on the staple foods (Neumann 163). People were suffering and Marie Antoinette was an easy target for them to relocate their unhappiness. The seeds of the Revolution had already been planted and there would be no drought to stop them from robustly exploding from the Earth.

Marie Antoinette’s very existence had always fueled the rage of the French, but the hatred toward her had reached an all-time high. To attempt to reduce the vicious attacks aimed at the royal family’s spending habits, Marie Antoinette took drastic measures to cut back her spending and par down her wardrobe. In light of her recent necklace drama, she stopped wearing diamonds completely. Her style changed from ornate and daring to simplistic. Instead of the pastel shades she had worn in her youth, she started to favor wearing darker colors. Marie Antoinette’s early carefree days at Versailles were gone forever and her new wardrobe was symbolic of this shift in mood. The Queen’s dramatic cutbacks resulted in a savings of 1,200,600 livres in 1788 alone (Weber 184). This accomplishment was not celebrated, however, and furthered her unpopularity. Her change in lifestyle was unpopular with the royal court and aristocrats who lost their charges and “blamed Marie Antoinette for their diminished income and prestige, even as they disparaged her as Madame Déficit” (184). Meanwhile, Marie Antoinette’s shift to a more simplistic style was as emulated as her old splashy fashions used to be. Aristocratic chronicler Félix de Montjoie noted that “even as the people were criticizing the Queen for her outfits, they continued frenetically to imitate her” (186).

It seemed as though Marie Antoinette truly could not win. Loving to hate her had become an essential form of entertainment for people from all ranks of society. She had been made public enemy #1, and in spite of her efforts and spending cutbacks, there was no way to salvage her reputation or change her fate. The Queen was well aware of the unstoppable landslide that had begun. She was heading into the last and darkest phase of her life with a sense of exhaustion and doom. Stefan Zweig notes that “Within two or three years after the necklace affair, Marie Antoinette’s reputation had been damaged beyond recall. She was regarded as the most lascivious, the most depraved, the most crafty, the most tyrannical woman in France; whereas Madame de la Motte, a condemned and branded felon, was looked upon as guiltless and virtuous” (256). The necklace affair continued to haunt Marie Antoinette when Jeanne de la Motte escaped from prison, fled to London, and published her memoirs in 1789. In these, she maintained her longstanding claim that she was innocent and had been duped by the Queen. Though the book was banned in France, people still managed to get their hands on it and used it to further justify their hatred toward Marie Antoinette (Memoirs of the Countess De Valois de la Motte).

John Hardman notes that in the years after the diamond necklace affair, Marie Antoinette was no longer as carefree as she had been in her youth. He describes that “There had always been a frenetic quality to her gaiety, brittleness in her laughter. Now she was pensive, even melancholy. Her carelessness had made her unpopular and her unpopularity made her serious, not to appease public opinion but because it made her sad” (159). Despite this sadness, Marie Antoinette did not withdraw from public life. Instead, she forged forward on a path that would anger her enemies even more; becoming a more serious part of her husband’s government.

In 1787, Louis XVI’s favorite minister Vergennes died leaving a gap in his administration that could only be filled by the person he trusted the most in life. Marie Antoinette swiftly grasped this opportunity, and to the astonishment of the other ministers, Louis XVI would only make his most important political decisions with her approval. Caroline Weber states that “Whereas she had once approximated real political “credit” principally through her costumes and expenditures, she was now, for the first time, actively helping to shape the policies of her husband’s government” (186).

An Avalanche of Slander and Defamation

Men had already demonized Marie Antoinette because of her gender for quite some time and her political involvement only increased these sexist attacks. Though the Revolution represented freedom, its resulting freedom highlighted the gender inequalities that contributed to the Queen’s demise. R.B. Rose writes that “the French Revolution was a bourgeois revolution: the bourgeois revolution was a revolution for and by men: therefore the French Revolution was a revolution against women” (191). Though men were leading the movement, they knew that women could easily use their sexuality to sway powerful men in their decision-making. Marie Antoinette was being taken more seriously as a threat considering her new position, and anti-monarchists intensified their public slander against the Queen by using her sexuality against her in unimaginable ways.

The French revolutionaries certainly had many legitimate reasons to be unhappy with their situation, but the aftermath of the diamond necklace affair marked a significant turning point in their ferocious smear campaigns against the Queen. Marie Antoinette had always been the frequent target of street libelles that used her likeness in pornography and made vile, slanderous accusations about her character, but now the monstrous claims made in these libelles began to intensify, using her womanhood against her in the most disturbing ways possible. Many depictions showed Marie Antoinette as a nymphomanic, having an insatiable sexual appetite and seeking sexual favors from her servants, brother-in-law, other women, court nobles, and most disturbingly, her own children. In addition to distributing pornographic imagery of Marie Antoinette, these libelles also featured essays with quotes from “inside palace sources” that weaponized nearly everything from the Queen’s reign against her, including the fact that it had taken her eleven years to produce an heir.

Historian Robert Darnton notes that the “Avalanche of defamation” aimed at Marie Antoinette between 1789 and her death has “no parallel in the history of vilification” (The Affair of the Diamond Necklace). Unlike changing her spending habits or her fashion style, the one thing Marie Antoinette could not change was her gender.

No Escape

Even after her imprisonment, men unabashedly used the propaganda that had been in libelles as means to convict the Queen. During her 1793 trial in front of the Revolutionary Tribunal, she was accused not only of dilapidating the finances of France and conspiring at home and abroad for the downfall of Frenchman, but committing incest with her son (Abner 14-36). It would have been unthinkable for a man to be accused of such a thing in a political trial, but nothing was off limits for the Queen. Marie Antoinette had been condemned even before her trial started. There was no escaping the guilty verdict that was swayed more by longstanding hatred for the Queen than justice.

The sexist libelles and years of being used as a scapegoat for all of the monarchies’ failures culminated with her being condemned to death by guillotine. Marie Antoinette said no words to the court upon hearing her fate and bravely met her death on October 16th, 1793. Early that morning, she wrote the last letter of her life to her sister-in-law, proclaiming “It is to you, my sister, that I write for the last time. I have just been condemned, not to a shameful death, for such is only for criminals, but to go and rejoin your brother. Innocent like him, I hope to show the same firmness in my last moments. I am calm, as one is when one’s conscience reproaches one with nothing…I ask forgiveness of all with whom I am acquainted, and of you, sister, in particular, for all the pain, which, without intending it, I may have caused you. I forgive all my enemies the injury they have done me. I here bid adieu to my aunts, and to all my brothers and sisters. I had friends! The idea of being separated from them forever, and of their afflictions, is the greatest grief I feel in dying; let them know at least, that to my latest moment, I thought of them. Adieu, my kind and tender sister; may this letter reach you. Always think of me; I embrace you with my whole heart, as well as those poor and dear children: O my God! how heart-rending it is to leave them forever! Adieu! Adieu! I must now occupy myself wholly with my spiritual duties.” (Full version here).

The Legacy

In the years to follow, many slanderous fictional works were written about Marie Antoinette, while royalist writers idealized their depiction of the Queen and her family with the goal of expiation. Despite efforts to rehabilitate her image, a genuine thirst remained for this tragic Queen to be remembered as a haughty tyrant. The public remained fascinated with the affair of the diamond necklace, and the storyline saw its first significant appearance in literature in Alexandre Dumas’ 1845 book series about Marie Antoinette. In Le Collier de la Reine, Dumas combines factual events with fiction and presents the Queen as having frivolous tendencies that outweigh her decision-making ability. In contrast, Dumas introduces Jeanne de la Motte’s character with far more humanity by telling the story of a damaged woman with a tragic background that justified her making the choices she did (1-240). Kalyn Rochelle Baldridge explains that “In his Marie-Antoinette series, Dumas did what he is known for: he took a moment from French history, and using the “historical sources” he had access to, he constructed an exciting fictional narrative to add meat to the skeleton of history. Dumas, unlike other writers we have seen and will still see, was not writing to rehabilitate the Queen’s image” (149). Dumas’ book was used as inspiration for numerous films about the diamond necklace affair.

In 1946’s The Queen’s Necklace directed by Marcel L’Herbier, Marie Antoinette’s character is glamorized but still portrayed as a victim of the scandal alongside Cardinal de Rohan. Jeanne de la Motte is accurately depicted as a crook. Even so, the character of the Queen in the film does not have many dimensions, making it hard for the audience sympathizes with her completely. Different versions of the key art for the film show Marie Antoinette lusting after the necklace and one promotional image depicts de la Motte on her knees while being apprehended by men. For those knowing little about the scandal, this imagery encourages the “let them eat cake” version of Marie Antoinette that is still so prevalent today. These images make it seem as though she lusted after the necklace, and even wore it, which is entirely inaccurate.

2001’s The Affair of the Necklace, directed by Charles Shyer is unapologetic in using some of the fictional elements of the scandal that Dumas created and builds upon them to turn Jeanne de la Motte into a noble heroine. The screenplay is shameless in its attempt to redeem de la Motte and leaves the audience feeling more sympathy for her than Marie Antoinette, even though she is shown being guillotined at the end. It is clear that even hundreds of years later, the image of Marie Antoinette that sells best is that of a greedy, head-strong queen whose bad decisions and lush lifestyle led to her death rather than that of a teenager who was thrust into an arranged marriage and expected to navigate the removed from reality world of Versailles with little guidance. Though some films made about Marie Antoinette are done with the intention to reverse misunderstandings about her life, they typically end up doing further damage to her reputation rather than rehabilitating it by mostly focusing on her frivolity.

While the events surrounding the diamond necklace affair certainly fanned the flames of the Revolution, some might argue that the unrest would have reached a breaking point even without being accelerated by scandal. Since the French people were dealing with significant hardships from drought and longstanding socioeconomic inequalities, there was bound to be a passionate movement to overthrow the monarchy regardless of this event transpiring. The monarchs’ extravagant spending habits had been ongoing and scrutinized long before Marie Antoinette ever married into the royal family. Even in the absence of her presence, they likely would have continued to anger and alienate the people of France in an irredeemable way. Though Marie Antoinette was and remains a convenient target for people to place blame, it is unlikely that the King and government would have been able to solve France’s problems without a revolution.

The diamond necklace affair remains emblematic of the excesses and problems that the French associated with the monarchy. The scandal unified those who felt trampled on by the systems in place and amplified their rage. Although Marie Antoinette had nothing to do with the creation of the necklace and never wanted it, this luxurious piece of jewelry will forever be a symbol of the eccentric and extravagant lifestyle that contributed to her downfall. Without this scandal and the public trial that followed, the French Revolution might not have happened as quickly or with as much heated passion as it did. The necklace merely acted as a key symbol of the excesses of the ancien régime and a catalyst that accelerated the people’s desires for change. Marie Antoinette suffered unfair scrutiny from the moment she arrived at Versailles, and the many years of character defamation that took a turn for the worst after this affair sealed her fate at the guillotine.

By the end of the Revolution, Boehmer and Bassenge’s history-altering necklace and the power and wealth that the monarchy had once amassed were broken into fragments. From these fragments, a new democracy emerged that rested on the values of liberty equality, and fraternity.

Today, the fragments of what was once the most dazzling piece of jewelry in France are now scattered across the world. The diamonds that hastened the demise of a queen have likely been set into new pieces that are resting inside jewelry boxes, holding a secret to which their owners will never be privy.

Bibliography

Neumann, J. “Great Historical Events That Were Significantly Affected by the Weather: 2, The Year Leading to the Revolution of 1789 in France.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, vol. 58, no. 2, 1977, pp. 163–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26218058. Accessed 31 Oct. 2022.

Anthony , Katharine. Marie Antionette. 1st ed., Alfred A Knopf New York, 1933.

Dumas, Alexandre. The Queen’s Necklace. Odin’s Library Classics, 2021.

Fraser, Antonia. Marie Antoinette: The Journey. Anchor Books, 2020.

Weber, Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. Picador, 2007.

“Répresentation Exacte Du Grand Collier En Brillants Des Srs. Boëhmer Et Bassenge Ca. 1785.” Metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/715394.

Hardman, John. Marie-Antoinette: The Making of a French Queen. Yale University Press, 2019. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvnwbx1c. Accessed 23 Oct. 2022.

Rose, R. B. “Feminism, Women and the French Revolution.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, vol. 21, no. 1, 1995, pp. 187–205. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41299020. Accessed 24 Oct. 2022.

“The Affair of the Diamond Necklace, 1784-1785.” Palace of Versailles, 23 Aug. 2018, https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/key-dates/affair-diamond-necklace-1784-1785.

“Memoirs of the Countess De Valois De La Motte: Containing a Compleat Justification of Her Conduct, and an Explanation of the Intrigues and Artifices Used against Her by Her Enemies, Relative to the Diamond Necklace : Comtesse De Valois De La Motte, Jeanne De Saint-Remy.” Internet Archive, 5 Nov. 2009, https://archive.org/details/MemoirsOfTheCountessDeValoisDeLaMotteContainingACompleat/page/n251/mode/2up.

History, Alpha. “The Affair of the Diamond Necklace.” French Revolution, 6 Oct. 2020, https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/affair-of-the-diamond-necklace/.

Baldridge, Kalyn Rochelle. L’AUGUSTE Autrichienne: Representations of Marie Antoinette In 19th Century French Literature and History. May 2016, https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10355/56208/research.pdf;sequence=2.

Conliffe, Ciaran. “Jeanne De La Motte, Noblewoman and Con Artist.” HeadStuff, 29 Oct. 2018, https://headstuff.org/culture/jeanne-de-la-motte-noblewoman-con-artist/.

“Collections Online: British Museum.” Collections Online | British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG212687.

“Memoirs of the Countess De Valois De La Motte: Containing a Compleat Justification of Her Conduct, and an Explanation of the Intrigues and Artifices Used against Her by Her Enemies, Relative to the Diamond Necklace : Comtesse De Valois De La Motte, Jeanne De Saint-Remy. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/MemoirsOfTheCountessDeValoisDeLaMotteContainingACompleat/page/n251/mode/2up.

Abner, Reed. “The Trial of Louis XVI, Late King of France and Marie Antoinette, His Queen .” The Trial, &c. of Louis XVI. Late King of France, and Marie Antoinette, His Queen. Embellished with Copper-Plate Engravings., https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N36069.0001.001/1:6?rgn=div1%3Bview.

Films

Shyer, Charles, director. The Affair of the Necklace. Warner Bros. Pictures/Summit Entertainment , 2001.

L’Herbier , Marcel, director. The Queen’s Necklace. Île De France Film, 1946.